# Let's setup the imports we'll need first

import altair as alt

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import seaborn as sns

from matplotlib import pyplot as plt

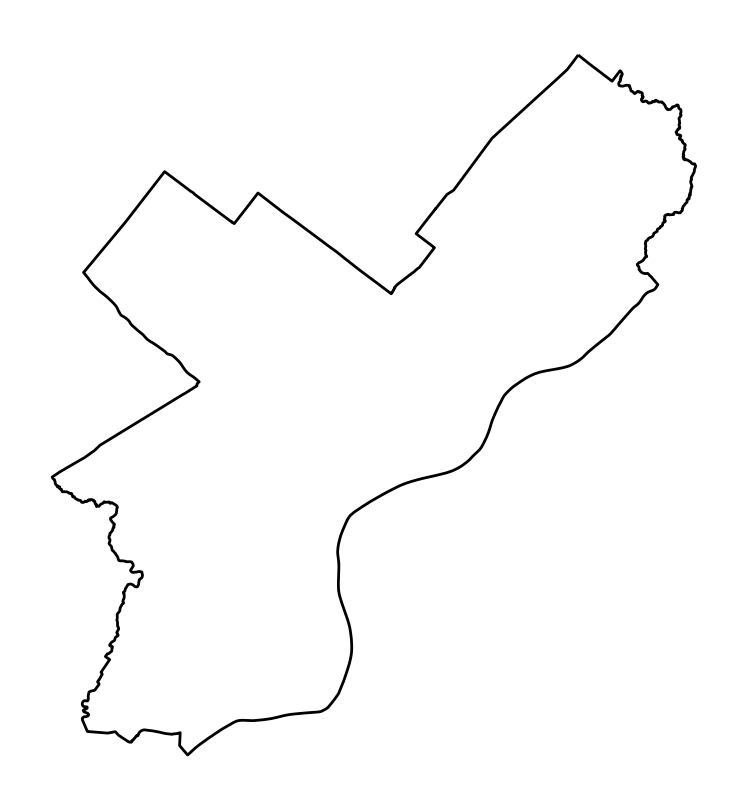

%matplotlib inlineWeek 3B: Intro to Geospatial Data Analysis with GeoPandas

- Section 401

- Sep 20, 2023

Housekeeping

- Homework #1 due on Monday (9/25)

- Homework #2 will be assigned same day

- Choose a dataset to visualize and explore

- OpenDataPhilly or one your choosing

- Email me if you want to analyze one that’s not on OpenDataPhilly

Agenda for today

- Introduction to GeoPandas and vector data

- Spatial relationships and joins

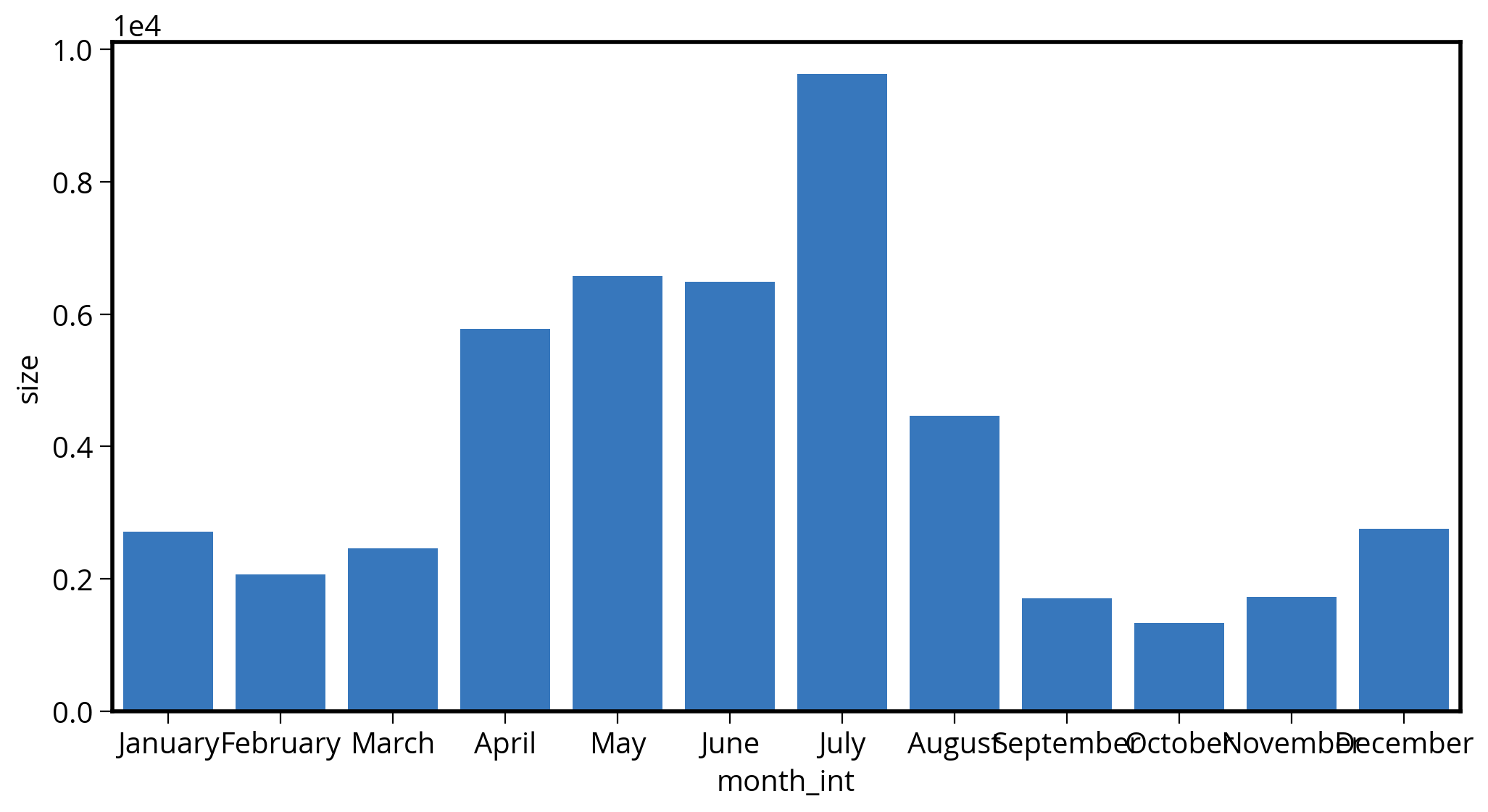

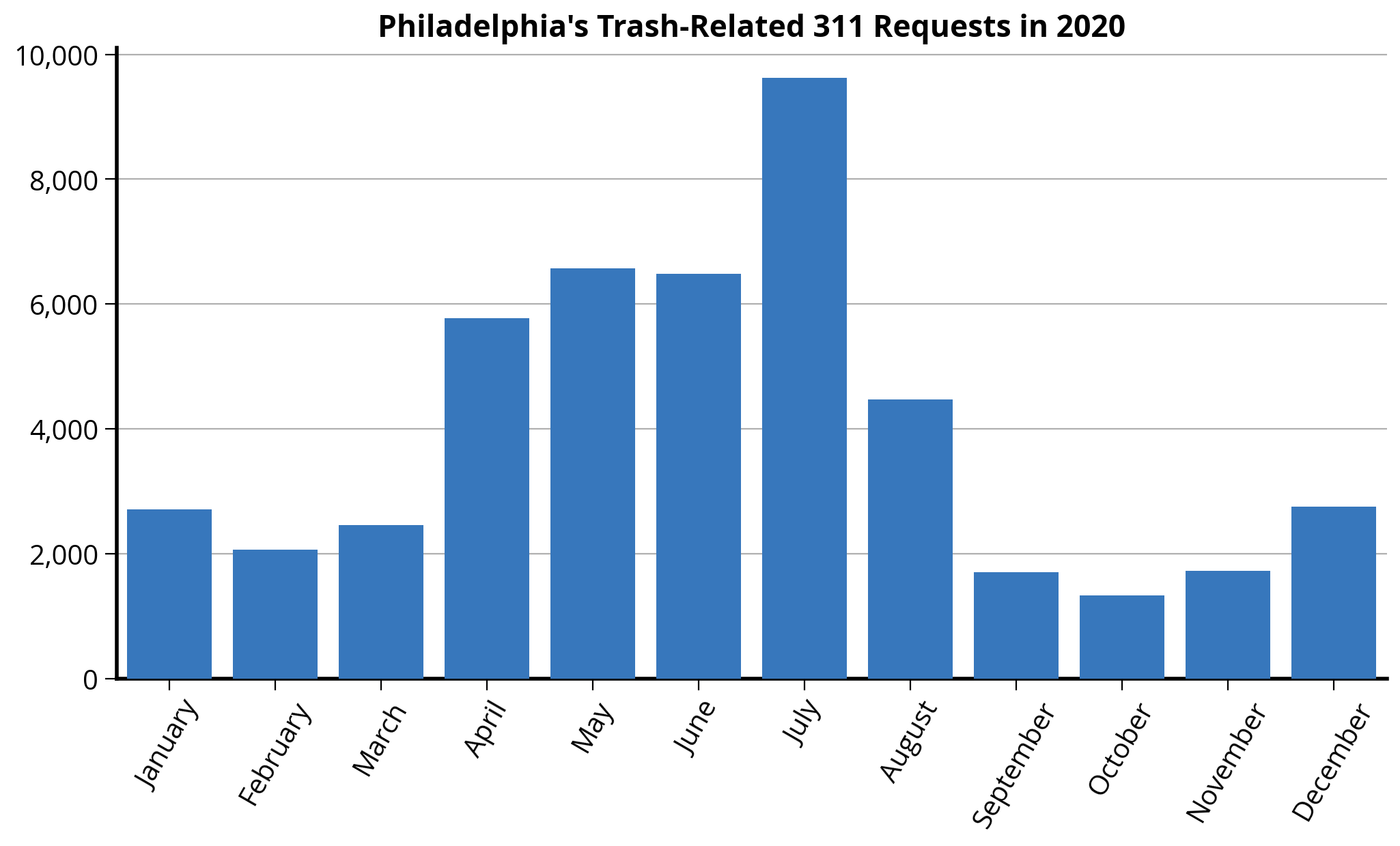

We’ll continue geospatial analysis next week, with: - Visualization for geospatial data - Demo: 311 requests by neighborhood in Philadelphia - Exercise: Property assessments by neighborhood

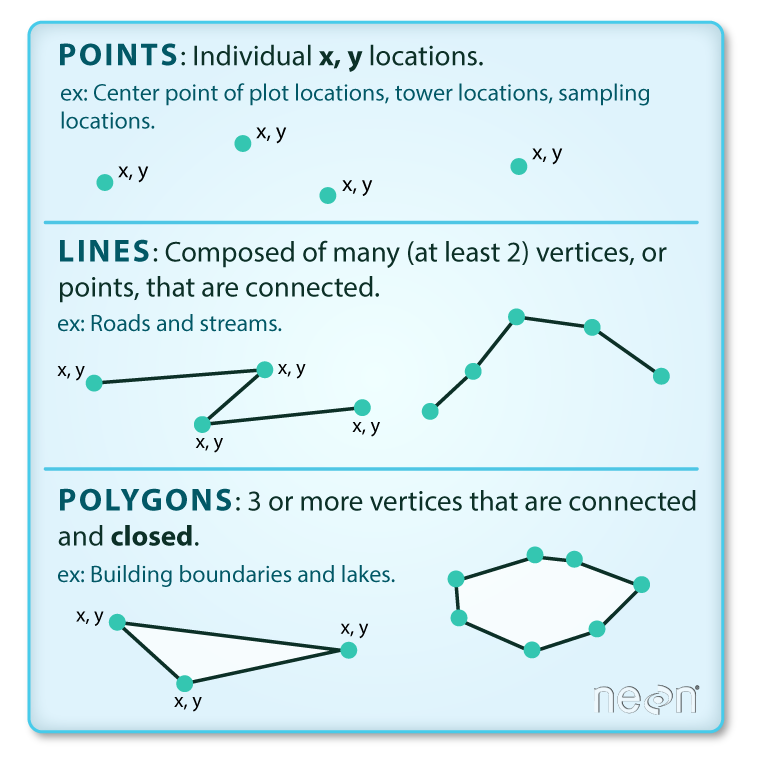

Part 1: Vector geospatial data in Python

- Vector refers to discrete geometric entities

- The Open Geospatial Consortium has standardized a set of simple features

- Includes points, lines, and polygons

A couple of terminology notes

- A feature refers to both the geometry and attributes of specific piece of vector data

- A feature collection is a list, or collection, of features

Both terms are very common in Python geospatial software.

Common formats for vector datasets

1. A shapefile

Actually several files with the same common prefix.

Mandatory files:

- .shp: the file containing the geometries

- .shx: the file that indexes the geometry

- .dbf: tabular data format storing the attributes for each geometry

And many optional files for documentation, projection information, etc.

Let’s take a look at an example shapefile:

We’ll use the %ls command to list out all of the files in an example shapefile in the data/ folder

%ls "data/ne_110m_admin_0_countries/"ne_110m_admin_0_countries.cpg ne_110m_admin_0_countries.shp

ne_110m_admin_0_countries.dbf ne_110m_admin_0_countries.shx

ne_110m_admin_0_countries.prj2. The GeoJSON file

- Stores simple features in a JSON format

- Arose due to the prevalence of the JSON format, especially on the web

- GitHub lets you view GeoJSON files natively. See Philadelphia ZIP Codes in the

data/folder of this week’s repo. - http://geojson.io provides interactive creation and viewing of small GeoJSON files

Analyzing vector data with GeoPandas

geopandas provides a simple, intuitive for the main types of geospatial vector file formats

# The import statement

import geopandas as gpdExample: Let’s load a shape file of countries in the world…

We can use the read_file() function to read shapefiles and GeoJSON files.

# Read the shape file, giving the name of the directory

countries = gpd.read_file("./data/ne_110m_admin_0_countries")countries.head()| iso_a3 | name | continent | pop_est | gdp_md_est | geometry | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | AFG | Afghanistan | Asia | 34124811.0 | 64080.0 | POLYGON ((61.21082 35.65007, 62.23065 35.27066... |

| 1 | AGO | Angola | Africa | 29310273.0 | 189000.0 | MULTIPOLYGON (((23.90415 -11.72228, 24.07991 -... |

| 2 | ALB | Albania | Europe | 3047987.0 | 33900.0 | POLYGON ((21.02004 40.84273, 20.99999 40.58000... |

| 3 | ARE | United Arab Emirates | Asia | 6072475.0 | 667200.0 | POLYGON ((51.57952 24.24550, 51.75744 24.29407... |

| 4 | ARG | Argentina | South America | 44293293.0 | 879400.0 | MULTIPOLYGON (((-66.95992 -54.89681, -67.56244... |

type(countries)geopandas.geodataframe.GeoDataFrameWhat’s a GeoDataFrame?

Just like a DataFrame but with a new, special geometry column:

Print out the first 10 entires of the “geometry” column:

countries["geometry"].head(n=10)0 POLYGON ((61.21082 35.65007, 62.23065 35.27066...

1 MULTIPOLYGON (((23.90415 -11.72228, 24.07991 -...

2 POLYGON ((21.02004 40.84273, 20.99999 40.58000...

3 POLYGON ((51.57952 24.24550, 51.75744 24.29407...

4 MULTIPOLYGON (((-66.95992 -54.89681, -67.56244...

5 POLYGON ((43.58275 41.09214, 44.97248 41.24813...

6 MULTIPOLYGON (((-59.57209 -80.04018, -59.86585...

7 POLYGON ((68.93500 -48.62500, 69.58000 -48.940...

8 MULTIPOLYGON (((145.39798 -40.79255, 146.36412...

9 POLYGON ((16.97967 48.12350, 16.90375 47.71487...

Name: geometry, dtype: geometryTake a look at the first geometry polygon by using the .iloc[] selector:

countries['geometry'].iloc[0]We can still leverage the power of pandas…

Calculate the total world population:

countries["pop_est"].sum() / 1e9 # In billions7.383089462Calculate the total population on each continent:

grouped = countries.groupby("continent")

grouped<pandas.core.groupby.generic.DataFrameGroupBy object at 0x17f287b80>The groupby() function does not return a DataFrame — you need to call sum(), mean() etc, or apply() a function to get your desired result!

Access the “pop_est” column from the groupby variable (“grouped”) and then call the .sum() function to calculate our desired statistic:

pop_by_continent = grouped["pop_est"].sum()

pop_by_continentcontinent

Africa 1.219176e+09

Antarctica 4.050000e+03

Asia 4.389145e+09

Europe 7.463985e+08

North America 5.730421e+08

Oceania 3.678284e+07

Seven seas (open ocean) 1.400000e+02

South America 4.185407e+08

Name: pop_est, dtype: float64# Sort values

pop_by_continent.sort_values(ascending=False, inplace=True)

# Output sorted values from cell

pop_by_continent / 1e9continent

Asia 4.389145e+00

Africa 1.219176e+00

Europe 7.463985e-01

North America 5.730421e-01

South America 4.185407e-01

Oceania 3.678284e-02

Antarctica 4.050000e-06

Seven seas (open ocean) 1.400000e-07

Name: pop_est, dtype: float64Filter the data frame based on a boolean selection:

# Is the country name USA?

is_USA = countries["name"] == "United States of America"

is_USA0 False

1 False

2 False

3 False

4 False

...

172 False

173 False

174 False

175 False

176 False

Name: name, Length: 177, dtype: bool# Get the row with USA

USA = countries.loc[is_USA]

USA| iso_a3 | name | continent | pop_est | gdp_md_est | geometry | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 168 | USA | United States of America | North America | 326625791.0 | 18560000.0 | MULTIPOLYGON (((-122.84000 49.00000, -120.0000... |

USA.squeeze().geometryThe squeeze() function does just one it sounds like: if you have a DataFrame with only one row, it will “squeeze” the row dimension by removing it, returning just a Series object:

# Squeeze

USA = USA.squeeze()

# Print out the types

print("The type of USA is: ", type(USA))

# Output

USAThe type of USA is: <class 'pandas.core.series.Series'>iso_a3 USA

name United States of America

continent North America

pop_est 326625791.0

gdp_md_est 18560000.0

geometry MULTIPOLYGON (((-122.84000000000005 49.0000000...

Name: 168, dtype: objectThe simple features (Lines, Points, Polygons) are implemented by the shapely library

USAiso_a3 USA

name United States of America

continent North America

pop_est 326625791.0

gdp_md_est 18560000.0

geometry MULTIPOLYGON (((-122.84000000000005 49.0000000...

Name: 168, dtype: objecttype(USA.geometry)shapely.geometry.multipolygon.MultiPolygonJupyterLab renders shapely geometries automatically:

# a mini USA

USA.geometryHow does geopandas handle coordinate systems and map projections?

A coordinate reference system (CRS) relates the position of a geometry object on the spherical earth to its two-dimensional coordinates.

A GeoDataFrame or GeoSeries has a .crs attribute which specifies the coordinate reference system.

countries.crs<Geographic 2D CRS: EPSG:4326>

Name: WGS 84

Axis Info [ellipsoidal]:

- Lat[north]: Geodetic latitude (degree)

- Lon[east]: Geodetic longitude (degree)

Area of Use:

- name: World.

- bounds: (-180.0, -90.0, 180.0, 90.0)

Datum: World Geodetic System 1984 ensemble

- Ellipsoid: WGS 84

- Prime Meridian: GreenwichThe EPSG=4326 CRS

- EPSG 4326 is known as WGS 84 where

xandyare longitude and latitude. - It is is the default coordinate system for GPS systems.

- It’s also known as Plate Carrée or equirectangular

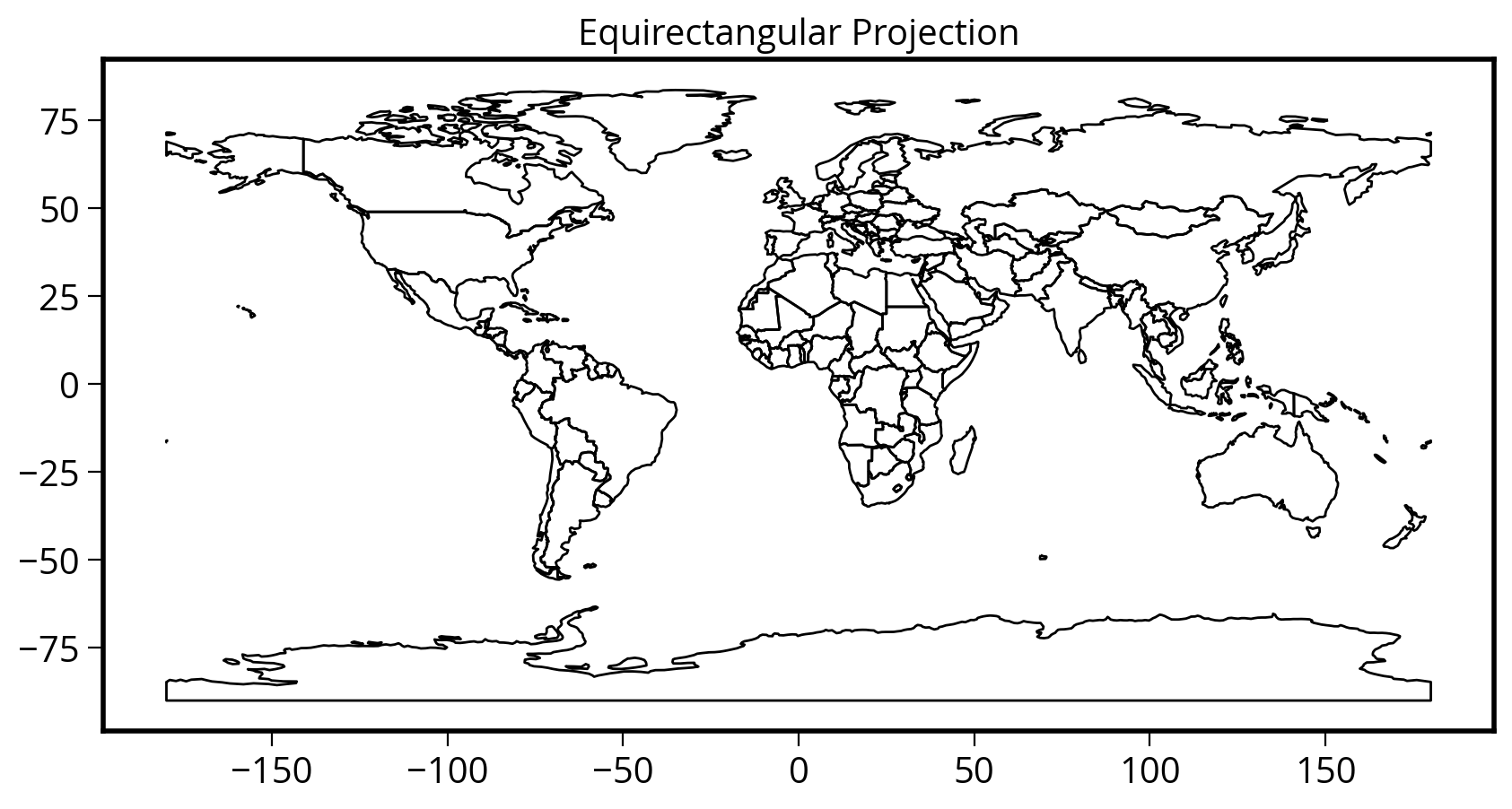

How to plot all of the geometries at once?

Use the plot() function to get a quick and dirty plot of all of the geometry features.

Note: the plot() returns the current maplotlib axes, allowing you to format the chart after plotting.

# Create a figure and axes

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(10, 6))

# Plot the countries on our axes

ax = countries.plot(ax=ax, facecolor="none", edgecolor="black")

# Add a title

ax.set_title("Equirectangular Projection");

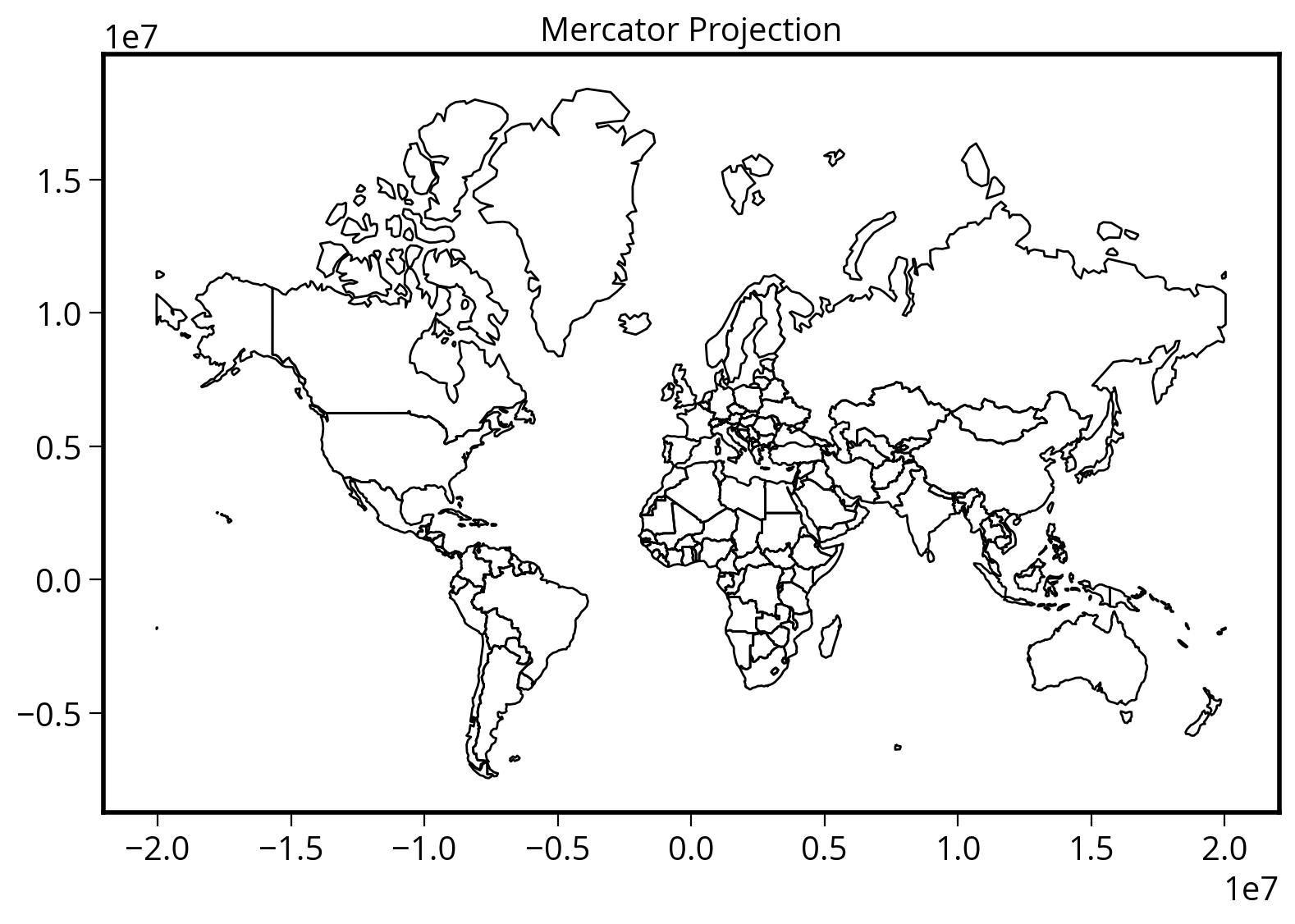

Can we convert to other coordinate systems?

Use the df.to_crs() function! The most well-known projections can be specified by their EPSG code.

Geopandas documentation on re-projecting: Managing Projections

Let’s convert to the Mercator projection

# Remove Antartica, as the Mercator projection

# cannot deal with the poles

no_antarctica = countries.loc[(countries["name"] != "Antarctica")]# Two ways to specify the EPSG code

countries_mercator = no_antarctica.to_crs(epsg=3395)

# Alternatively:

# countries_mercator = no_antartica.to_crs("EPSG:3395")countries_mercator.head()| iso_a3 | name | continent | pop_est | gdp_md_est | geometry | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | AFG | Afghanistan | Asia | 34124811.0 | 64080.0 | POLYGON ((6813956.990 4227673.562, 6927484.435... |

| 1 | AGO | Angola | Africa | 29310273.0 | 189000.0 | MULTIPOLYGON (((2660998.216 -1305442.810, 2680... |

| 2 | ALB | Albania | Europe | 3047987.0 | 33900.0 | POLYGON ((2339940.185 4961221.199, 2337708.178... |

| 3 | ARE | United Arab Emirates | Asia | 6072475.0 | 667200.0 | POLYGON ((5741805.754 2765811.385, 5761611.935... |

| 4 | ARG | Argentina | South America | 44293293.0 | 879400.0 | MULTIPOLYGON (((-7453944.198 -7306880.704, -75... |

Take a look at the values in the “geometry” column above. The magnitude of the coordinates changed! This is a quick and easy way to tell if the re-projection worked properly!

Now let’s plot it!

The easy way…with geopandas built-in plot() function

# Initialize the figure and axes

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(10, 6))

# Use built-in plot() of the GeoDataFrame

ax = countries_mercator.plot(ax=ax, facecolor="none", edgecolor="black")

# Add a title

ax.set_title("Mercator Projection");

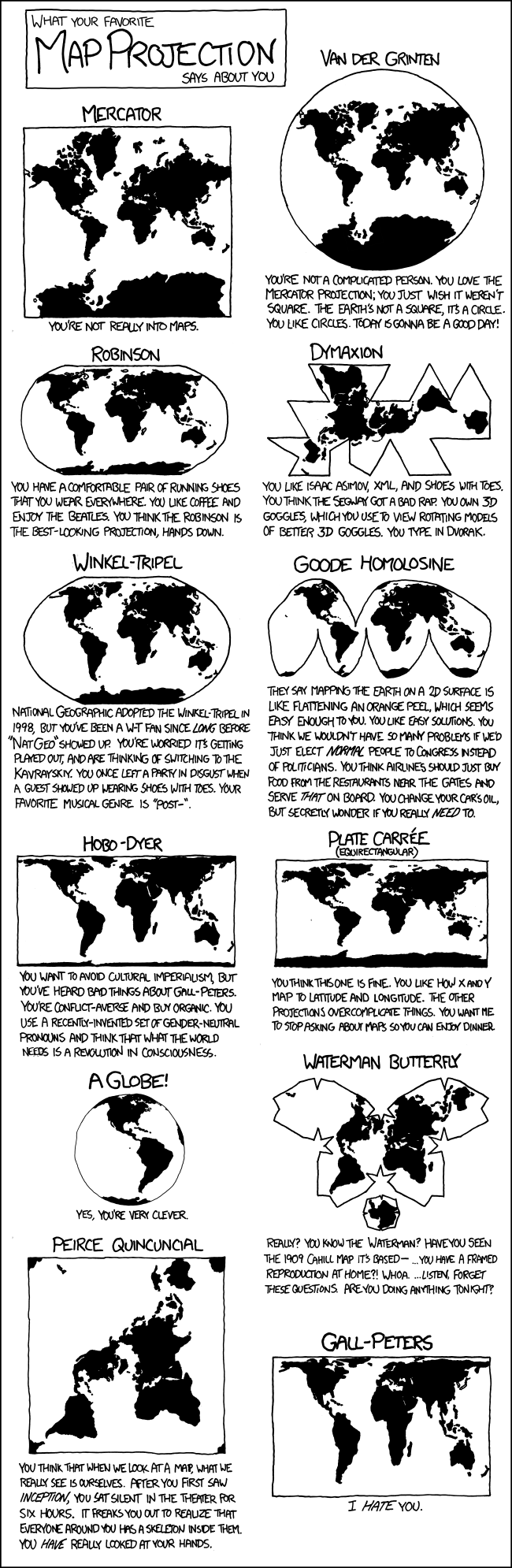

Which one is your favorite?

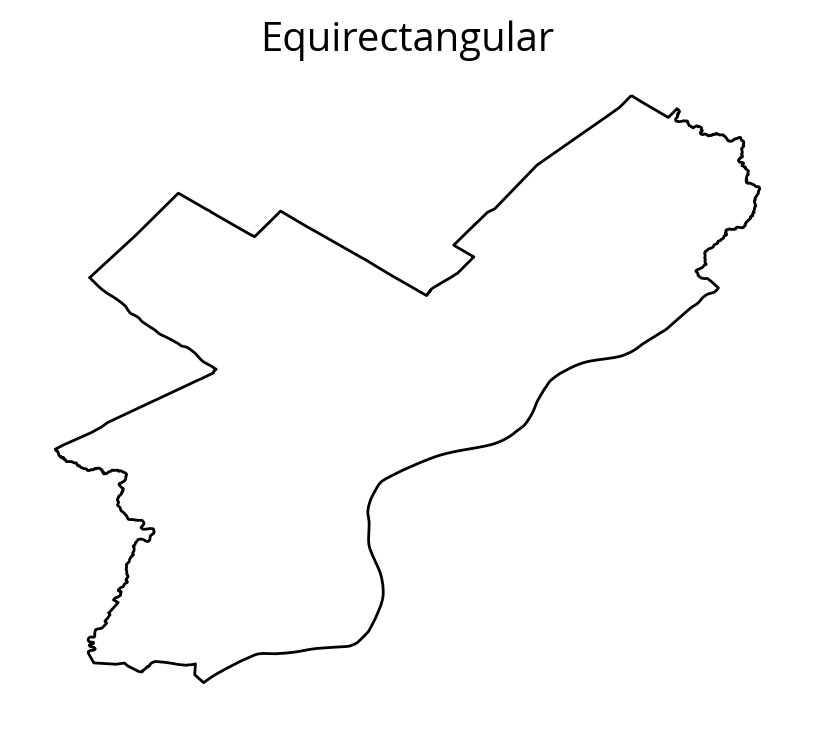

- For city-based data, the Web Mercator CRS (EPSG=3857) is best. This CRS became popular after Google Maps adopted it.

- You can also use a CRS specific to individual states, e.g., the PA State Plane EPSG=2272 is a good option for Philadelphia

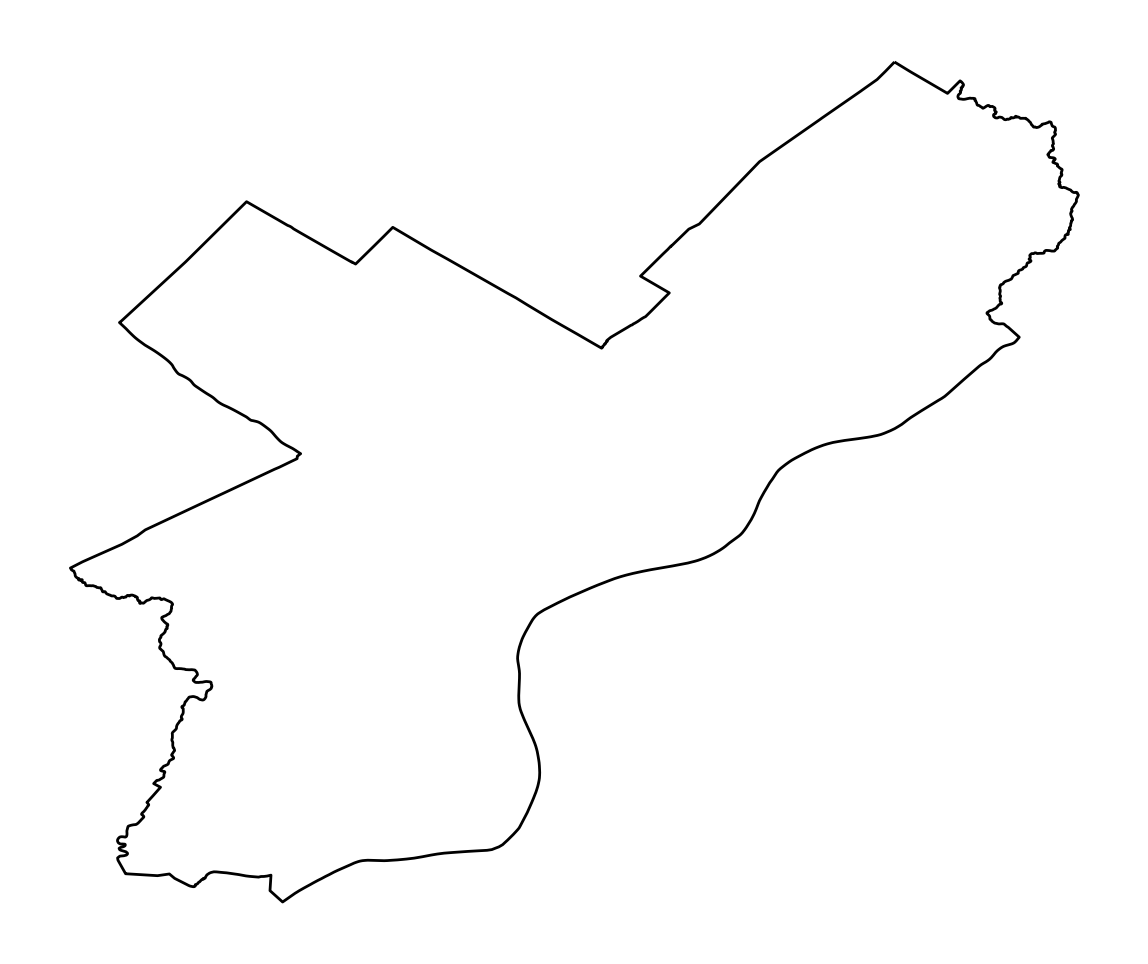

Let’s load the city limits for Philadelphia

We’ll use the provided City_Limits shape file in the data/ folder

city_limits = gpd.read_file("./data/City_Limits")

city_limits| OBJECTID | Shape__Are | Shape__Len | geometry | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 0.038911 | 1.259687 | POLYGON ((-75.01497 40.13793, -75.01456 40.137... |

What’s the CRS?

Use the .crs attribute to find out!

city_limits.crs<Geographic 2D CRS: EPSG:4326>

Name: WGS 84

Axis Info [ellipsoidal]:

- Lat[north]: Geodetic latitude (degree)

- Lon[east]: Geodetic longitude (degree)

Area of Use:

- name: World.

- bounds: (-180.0, -90.0, 180.0, 90.0)

Datum: World Geodetic System 1984 ensemble

- Ellipsoid: WGS 84

- Prime Meridian: GreenwichPlot it with the EPSG=4326 CRS:

# Create our figure and axes

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(5, 5))

# Plot

city_limits.plot(ax=ax, facecolor="none", edgecolor="black")

# Format

ax.set_title("Equirectangular")

ax.set_axis_off() # This will remove the axes completely

ax.set_aspect("equal") # This forces an equal aspect ratio

This is not what Philadelphia looks like..

Let’s try EPSG=3857 instead:

# Create the figure

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(5, 5))

# Convert to EPSG:3857

city_limits_3857 = city_limits.to_crs(epsg=3857)

# Plot and format

city_limits_3857.plot(ax=ax, facecolor="none", edgecolor="black")

ax.set_title("Web Mercator")

ax.set_axis_off()

ax.set_aspect("equal");

The equirectangular CRS (EPSG=4326) is often used by default and will make cities appear wider and flatter than they really are.

Saving GeoDataFrames

Use the to_file() function and specify the driver.

# ESRI shape file

city_limits_3857.to_file("./data/city_limits_3857", driver="Shapefile")# GeoJSON is also an option

city_limits_3857.to_file("./data/city_limits_3857.geojson", driver="GeoJSON")How about as a CSV file?

Yes, but reading requires more work…

# save a csv file

city_limits_3857.to_csv("./data/city_limits_3857.csv", index=False)df = pd.read_csv("./data/city_limits_3857.csv")

df.head()| OBJECTID | Shape__Are | Shape__Len | geometry | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 0.038911 | 1.259687 | POLYGON ((-8350627.97509646 4886006.88680784, ... |

Looks similar…

But, the “geometry” column is just stored as a string…it’s not a shapely Polygon

df.geometry0 POLYGON ((-8350627.97509646 4886006.88680784, ...

Name: geometry, dtype: objectUse shapely to parse the string version of the polygons

from shapely import wkt

# wkt.loads will convert from string to Polygon object

df["geometry"] = df["geometry"].apply(wkt.loads)df.geometry.iloc[0]Success!

Converting from a DataFrame to a GeoDataFrame

We can initialize the GeoDataFrame directly from a DataFrame but we need to specify two things:

- The name of the “geometry” column

- The CRS of the “geometry” column

The CRS that you specify when you create the GeoDataFrame must match the CRS of the data. It is not the CRS that you wish the data was in. If you would like to convert to a different CRS, you’ll need to call the .to_crs() after creating your GeoDataFrame.

In this case, the geometry column was saved in Web Mercator EPSG=3857

# Make specifying the name of the geometry column and CRS

gdf = gpd.GeoDataFrame(df, geometry="geometry", crs="EPSG:3857")

# Now plot

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(5, 5))

ax = gdf.plot(ax=ax, facecolor="none", edgecolor="black")

ax.set_axis_off()

ax.set_aspect("equal")

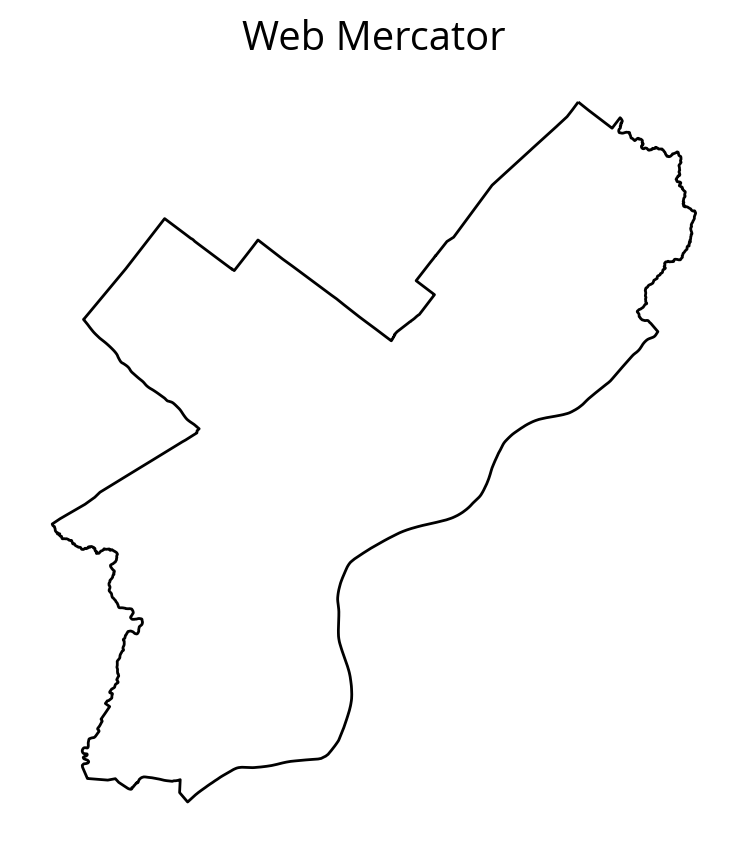

Let’s convert back to 4326 and plot

The tilt should be a bit more obvious now…

ax = gdf.to_crs(epsg=4326).plot(facecolor="none", edgecolor="black")

ax.set_axis_off()

ax.set_aspect("equal")

- I didn’t use

plt.subplots()here to create a figure/axes – I let geopandas automatically make one - I’ve chained together the

to_crs()and.plot()functions in one line - The

.plot()function returns the axes object that geopandas used to plot — this lets you customizes the axes after plotting

So, when should you use GeoPandas?

- For exploratory data analysis and visualization, including in Jupyter notebooks

- Pre-processing data to be fed into a desktop GIS program

- For compact, readable, and reproducible code

- If you’re comfortable with Pandas and/or R data frames.

When it may not be the best tool:

- For polished multilayer map creation — one option is to use a desktop GIS like QGIS.

- If you need very high performance — geopandas can be slow compared to other GIS software.

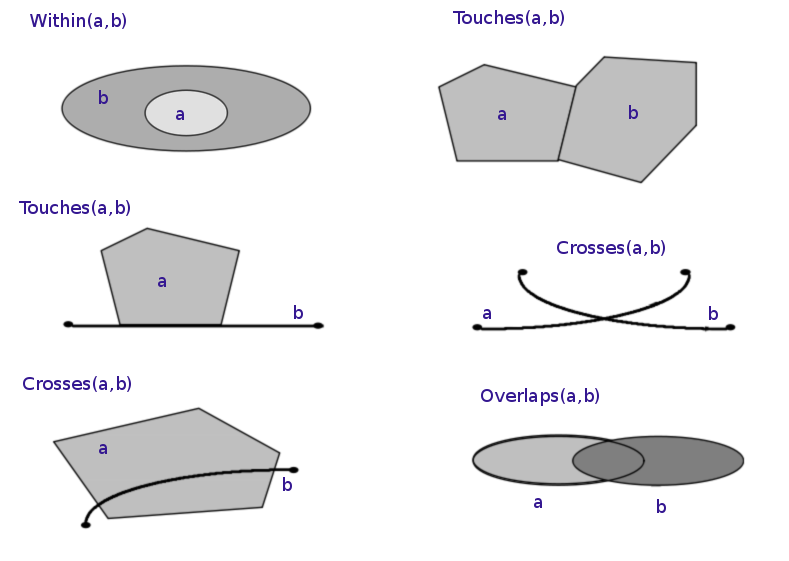

Part 2: Spatial Relationships and Joins

Let’s explore joins and merges between GeoDataFrames based on geospatial relationships…

# Load some cities data from the data/ folder

cities = gpd.read_file("./data/ne_110m_populated_places")cities| name | geometry | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Vatican City | POINT (12.45339 41.90328) |

| 1 | San Marino | POINT (12.44177 43.93610) |

| 2 | Vaduz | POINT (9.51667 47.13372) |

| 3 | Lobamba | POINT (31.20000 -26.46667) |

| 4 | Luxembourg | POINT (6.13000 49.61166) |

| ... | ... | ... |

| 238 | Rio de Janeiro | POINT (-43.22697 -22.92308) |

| 239 | São Paulo | POINT (-46.62697 -23.55673) |

| 240 | Sydney | POINT (151.18323 -33.91807) |

| 241 | Singapore | POINT (103.85387 1.29498) |

| 242 | Hong Kong | POINT (114.18306 22.30693) |

243 rows × 2 columns

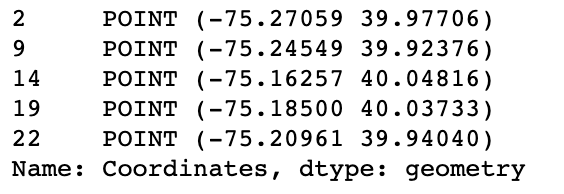

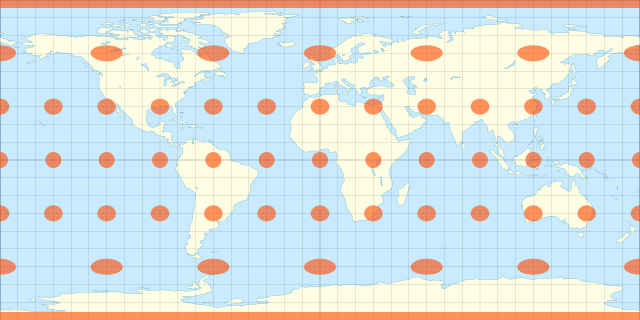

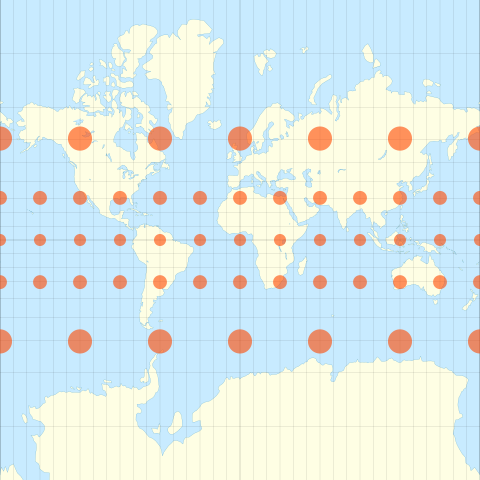

(Image by Krauss, CC BY-SA 3.0)

All of these operations are available as functions of a GeoDataFrame.

A quick example

What country is New York in?

Spoiler: the USA

# Select the Point representing New York City

new_york = cities.loc[cities["name"] == "New York"].geometry.squeeze()

new_yorktype(new_york)shapely.geometry.point.Pointcountries.contains(new_york)0 False

1 False

2 False

3 False

4 False

...

172 False

173 False

174 False

175 False

176 False

Length: 177, dtype: bool# Find the country that contains New York

countries.loc[countries.contains(new_york)]| iso_a3 | name | continent | pop_est | gdp_md_est | geometry | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 168 | USA | United States of America | North America | 326625791.0 | 18560000.0 | MULTIPOLYGON (((-122.84000 49.00000, -120.0000... |

# Get the geometry column of the country containing NYC

USA = countries.loc[countries.contains(new_york)].squeeze().geometry

USAThe .loc[] function can take the index selector as the first argument, and the name of a column as a second argument (separated by a comma)

type(USA)shapely.geometry.multipolygon.MultiPolygon# Is New York within the USA?

new_york.within(USA)TrueUSAReferences

The different functions for checking spatial relationships:

equalscontainscrossesdisjointintersectsoverlapstoucheswithincovers

See the shapely documentation for an overview of these methods.

1. The spatial join: sjoin()

SPATIAL JOIN = merging attributes from two geometry layers based on their spatial relationship

Different parts of this operations:

- The GeoDataFrame to which we want add information

- The GeoDataFrame that contains the information we want to add

- The spatial relationship we want to use to match both datasets (intersects, contains, within)

- The type of join: left or inner join

In this case, we want to join the cities dataframe, containing Point geometries, with the information of the countries dataframe, containing Polygon geometries.

To match cities with countries, we’ll use the within spatial relationship.

The geopandas.sjoin() function performs this operation:

joined = gpd.sjoin(

cities,

countries,

predicate="within",

how="left",

lsuffix="city",

rsuffix="country",

)joined.head()| name_city | geometry | index_country | iso_a3 | name_country | continent | pop_est | gdp_md_est | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Vatican City | POINT (12.45339 41.90328) | 79.0 | ITA | Italy | Europe | 62137802.0 | 2221000.0 |

| 1 | San Marino | POINT (12.44177 43.93610) | 79.0 | ITA | Italy | Europe | 62137802.0 | 2221000.0 |

| 2 | Vaduz | POINT (9.51667 47.13372) | 9.0 | AUT | Austria | Europe | 8754413.0 | 416600.0 |

| 3 | Lobamba | POINT (31.20000 -26.46667) | 152.0 | SWZ | Swaziland | Africa | 1467152.0 | 11060.0 |

| 4 | Luxembourg | POINT (6.13000 49.61166) | 97.0 | LUX | Luxembourg | Europe | 594130.0 | 58740.0 |

As we can see above, the attributes of the cities (left) and countries (right) have been merged based on whether the city is inside the country.

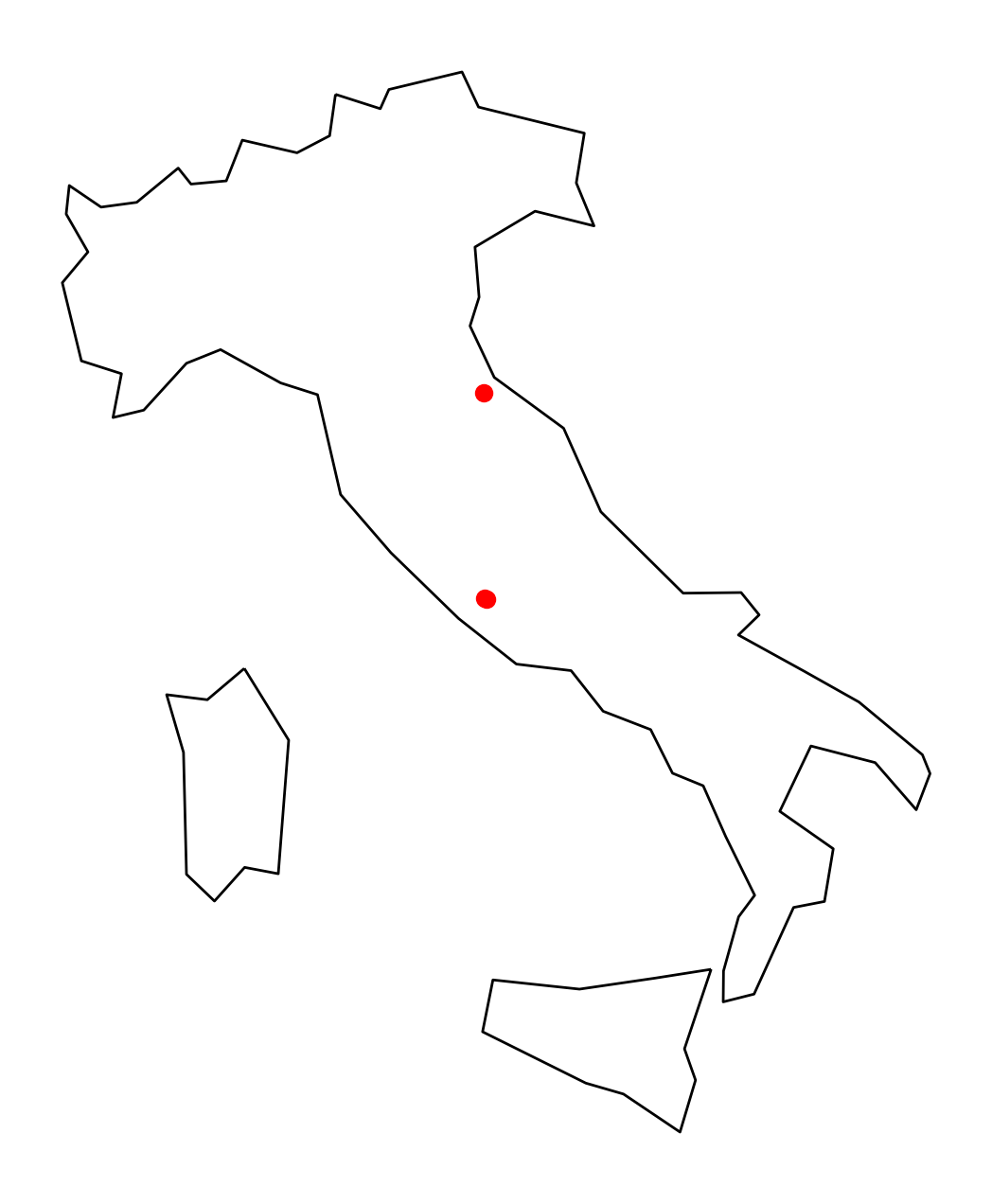

Let’s select cities in Italy only:

cities_in_italy = joined.loc[joined["name_country"] == "Italy"]

cities_in_italy| name_city | geometry | index_country | iso_a3 | name_country | continent | pop_est | gdp_md_est | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Vatican City | POINT (12.45339 41.90328) | 79.0 | ITA | Italy | Europe | 62137802.0 | 2221000.0 |

| 1 | San Marino | POINT (12.44177 43.93610) | 79.0 | ITA | Italy | Europe | 62137802.0 | 2221000.0 |

| 226 | Rome | POINT (12.48131 41.89790) | 79.0 | ITA | Italy | Europe | 62137802.0 | 2221000.0 |

# Extract Italy

italy = countries.loc[countries["name"] == "Italy"]

# Plot

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(8, 8))

italy.plot(ax=ax, facecolor="none", edgecolor="black")

ax.set_axis_off()

ax.set_aspect("equal")

# Plot the first city in the joined data frame (Vatican City)

# Use the same axes by passing in the ax=ax keyword

ax = cities_in_italy.plot(ax=ax, color="red")

2. Spatial overlay operation: overlay()

We can also perform the “join” operation on the geometries rather than just combining attributes.

The overlay() function combines geometries, e.g. by taking the intersection of the geometries.

Select all countries in Africa:

africa = countries.loc[countries["continent"] == "Africa"]africa.head()| iso_a3 | name | continent | pop_est | gdp_md_est | geometry | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | AGO | Angola | Africa | 29310273.0 | 189000.0 | MULTIPOLYGON (((23.90415 -11.72228, 24.07991 -... |

| 11 | BDI | Burundi | Africa | 11466756.0 | 7892.0 | POLYGON ((29.34000 -4.49998, 29.27638 -3.29391... |

| 13 | BEN | Benin | Africa | 11038805.0 | 24310.0 | POLYGON ((2.69170 6.25882, 1.86524 6.14216, 1.... |

| 14 | BFA | Burkina Faso | Africa | 20107509.0 | 32990.0 | POLYGON ((2.15447 11.94015, 1.93599 11.64115, ... |

| 25 | BWA | Botswana | Africa | 2214858.0 | 35900.0 | POLYGON ((29.43219 -22.09131, 28.01724 -22.827... |

What is the CRS?

africa.crs<Geographic 2D CRS: EPSG:4326>

Name: WGS 84

Axis Info [ellipsoidal]:

- Lat[north]: Geodetic latitude (degree)

- Lon[east]: Geodetic longitude (degree)

Area of Use:

- name: World.

- bounds: (-180.0, -90.0, 180.0, 90.0)

Datum: World Geodetic System 1984 ensemble

- Ellipsoid: WGS 84

- Prime Meridian: Greenwich# Let's transform to a CRS that uses meters

# instead of degrees (EPSG=3857)

africa = africa.to_crs(epsg=3857)

africa.crs<Projected CRS: EPSG:3857>

Name: WGS 84 / Pseudo-Mercator

Axis Info [cartesian]:

- X[east]: Easting (metre)

- Y[north]: Northing (metre)

Area of Use:

- name: World between 85.06°S and 85.06°N.

- bounds: (-180.0, -85.06, 180.0, 85.06)

Coordinate Operation:

- name: Popular Visualisation Pseudo-Mercator

- method: Popular Visualisation Pseudo Mercator

Datum: World Geodetic System 1984 ensemble

- Ellipsoid: WGS 84

- Prime Meridian: GreenwichPlot it:

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(8, 8))

africa.plot(ax=ax, facecolor="#b9f2b1")

ax.set_axis_off()

ax.set_aspect("equal")

# Important CRS needs to match!

cities_3857 = cities.to_crs(epsg=3857)# Create a copy of the GeoDataFrame

buffered_cities = cities_3857.copy()

# Add a buffer region of 250 km around all cities

buffered_cities["geometry"] = buffered_cities.buffer(250e3)Plot the difference of the two geometries

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(8, 8))

# Calculate the difference of the geometry sets

diff = gpd.overlay(

africa,

buffered_cities,

how="difference",

)

# Plot

diff.plot(facecolor="#b9f2b1", ax=ax)

ax.set_axis_off()

ax.set_aspect("equal")/Users/nhand/mambaforge/envs/musa-550-fall-2023/lib/python3.10/site-packages/shapely/constructive.py:181: RuntimeWarning: invalid value encountered in buffer

return lib.buffer(

/Users/nhand/mambaforge/envs/musa-550-fall-2023/lib/python3.10/site-packages/shapely/set_operations.py:77: RuntimeWarning: invalid value encountered in difference

return lib.difference(a, b, **kwargs)

# Data attributes are the same as the first data frame (africa)

# with an updated geometry column

diff.head()| iso_a3 | name | continent | pop_est | gdp_md_est | geometry | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | AGO | Angola | Africa | 29310273.0 | 189000.0 | MULTIPOLYGON (((2673464.087 -1449571.330, 2441... |

| 1 | BEN | Benin | Africa | 11038805.0 | 24310.0 | POLYGON ((100138.898 1231805.081, 138422.412 1... |

| 2 | BFA | Burkina Faso | Africa | 20107509.0 | 32990.0 | MULTIPOLYGON (((100138.898 1231805.081, 26368.... |

| 3 | BWA | Botswana | Africa | 2214858.0 | 35900.0 | POLYGON ((3065120.801 -2659823.621, 3061281.52... |

| 4 | CAF | Central African Rep. | Africa | 5625118.0 | 3206.0 | POLYGON ((1792937.514 836963.765, 1813457.017 ... |

Plot the intersection of the two geometries

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(8, 8))

# The intersection of the geometry sets

intersection = gpd.overlay(africa, buffered_cities, how="intersection")

# Plot

intersection.plot(ax=ax, facecolor="#b9f2b1")

ax.set_axis_off()

ax.set_aspect("equal")/Users/nhand/mambaforge/envs/musa-550-fall-2023/lib/python3.10/site-packages/shapely/constructive.py:181: RuntimeWarning: invalid value encountered in buffer

return lib.buffer(

/Users/nhand/mambaforge/envs/musa-550-fall-2023/lib/python3.10/site-packages/shapely/set_operations.py:133: RuntimeWarning: invalid value encountered in intersection

return lib.intersection(a, b, **kwargs)

Recap: spatial operations

- Spatial join: merge attributes from one data frame to another based on the spatial relationship

- Spatial overlay: creating new geometries based on spatial operation between both data frames (and not combining attributes of both data frames)

That’s it!

- We’ll continue our 311 example next week

- More geopandas and geospatial data analysis coming up

- See you on Monday next week!